Deep in the Heart of FRANCE

After over 50 years, Michael Webb revisits southwestern France.

I have fond memories of my first trip to the Dordogne, a region of southwestern France that takes its name from one of the three rivers that flow through softly rolling farmland studded with medieval towns and villages. A college friend and I found a congenial b&b in Laroque-Gageac, and raced around for a week, returning every evening for our host’s elaborate dinner, which might begin with a truffled omelette and continue on for six courses. That was 54 years ago, when our beds cost a pound a night, and board another pound.

The prices have jumped, but little else has changed: this is still a tranquil enclave of great beauty: the embodiment of la France profonde. For centuries it was a battleground of rival powers and sects; now it is an oasis of peace, uncorrupted by mass tourism. Penny and I had only a week before continuing on to Spain, so we chose two bases from which to range out every day along winding lanes and the occasional highway. There are no motorways and public transport is limited. Tour de France wannabees in brightly colored spandex labor up the steepest slopes and there are a few pilgrims with sticks and backpacks starting out on the long trek to Santiago. For guidance, I consulted the same classic account that inspired my first trip: Freda White’s Three Rivers of France. There’s a later edition with color pictures, but White’s descriptions are so vivid there’s no need of illustrations.

Monpazier market square | Photo: Michael Webb

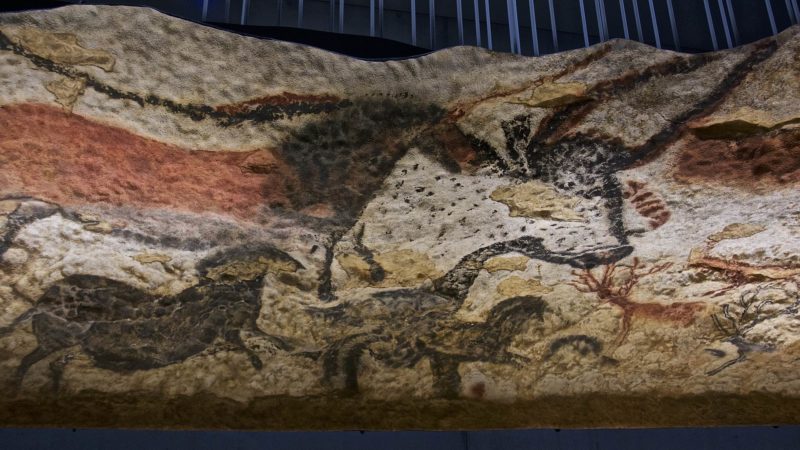

Our first stay was in the Edward 1er hotel in Monpazier, one of the best preserved bastides built by the English king of that name to guard his territory in the province of Aquitaine. A bastide was a walled grid of streets with a church and market square at the center, where settlers were protected from marauding armies; our hotel, built a century ago, is the newest building in town. From there we drove to the International Lascaux Centre, a new building that contains an exact replica of the painted caves that occupy the same hillside. Descending a rugged path we marveled at the bestiary that talented artists created on walls and ceilings 17,000 years ago. Small groups are guided through and then you are free to wander around explanatory displays on the creation and recreation of these primitive masterpieces.

Lascaux Center | Photo: Michael Webb

Before the French and English warred for possession of this country, there was a wave of prosperity that produced a rich legacy of Romanesque churches. Many doubled as fortresses, with massive stone walls and tiny windows set high up, but sculptors enriched them with intricate carvings, mixing biblical themes with a world of fantasy. The west door was often topped by a Last Judgement, where the dead rose from their graves to be sorted out, the virtuous off to heaven, the wicked to a hell of monsters, vats of boiling oil and devils with pitchforks. Many of these churches were attached to abbeys, and the finest of them all is at Moissac, where the double columns around the cloister have marvelously carved capitals.

Moissac capital | Photo: Michael Webb

We explored the picture-perfect villages of Martel and Carennac, the Romanesque churches of Beaulieu and Souillac, and the fortified Pont Valentré in Cahors, lunching riverside or in the squares that still host a weekly market within an open-sided medieval hall. The Chateau de Montal boasts a garden of geometrical topiary that was added in the 1970s to complement the elegant Renaissance facades. It was built by a noble lady for her son, who was killed in the wars, and she added an inscription high up beneath a gable, “Plus d’Espoir”—no more hope.

Chateau de Montal | Photo: Michael Webb

For our second stay we picked the Moulin de Conques, a converted water mill with a few rustic rooms and an outstanding restaurant, La Table d’Hervé—named for Hervé Busset, its young chef. The region is known for its gutsy food: foie gras and duck, wild mushrooms and potatoes sautéed in walnut oil. Hervé creates refined dishes from those ingredients, delighting the eye as much as the palette. Perched on a steep hill a few miles up the road is Conques: a stone village clustered around a great Romanesque abbey. Its monks stole the relics of St Foy, an early Christian martyr, from a rival foundation, growing rich as they packed in the pilgrims. The tympanum is one of the finest in France: a masterpiece of the stone-carver’s art, which retains traces of the original colors. Within the tall narrow nave are new windows recently created by Pierre Soulages.

Table d’Herve | Photo: Michael Webb

That prompted us to visit the Soulages Museum in the artist’s home town of Rodez. The galleries jut from a hillside and are clad in rusted steel, whose patina evokes one of Soulages’ somber paintings. The building was designed by RCR, a Pritzker-Prize winning firm from Spain, and the interior, with its soft light glinting off polished steel is a perfect fusion of art and architecture. Another museum, close by in St Ceré, celebrates the modern tapestries of Jean Lurçat. On our last day we paused at Estaing, a handsome town that straddles the River Lot. It was a peaceful scene, suddenly animated by a flotilla of kayaks, as brightly colored as the sports cyclists we kept overtaking. From there we headed south, across Norman Foster’s viaduct, a marvel of engineering that rises to the height of the Eiffel Tower above the base of the Millau gorge, and on into Catalonia.

Soulages museum | Photo: Michael Webb

Michael Webb

around the world.

Latest posts by Michael Webb

- DESTINATION: Revisiting the South of France - April 30, 2024

- Exploring the Czech Republic - January 29, 2024

- Rediscovering Morocco - April 6, 2022