Fusing Old and New in CHINA

In China, historic landmarks alternate with a few spectacular new buildings by top Western architects, which mark a sharp break with the past. On one side is the Forbidden City and the gardens of Suzhou, with their still ponds and moon gates; on the other are towers that twist and swoop as though they were alive. Both species can be exciting but, on a recent trip, I searched for the hybrid of old and new that indigenous architects are creating. Two Chinese friends traveled with me and helped find cool modern guest houses that felt far removed from the big chain hotels and the tourist hordes that overwhelm familiar sites.

In Beijing we stayed at the Twisting Courtyard, a three-room b&b that opens off a narrow alley through an unmarked door. Fifty years ago most of the capital was like this: a low-rise labyrinth of alleys (hutongs) and courtyard houses surrounding the Forbidden City, within and beyond the city walls. On my first visit, in 1988, the streets were full of bicycles, there were almost no cars, and the hutongs were full of peddlers, itinerant barbers, and old men listening to the crickets they kept in gourds. The destruction of old quarters was well underway even then and today most of the few surviving hutongs have been gentrified and are full of restaurants and souvenir shops. Ours preserved its authenticity and cheerful scruffiness, even though it is only a few hundred yards from the vast expanse of Tian’anmmen Square.

To create the Twisting Courtyard, Han Wenqian, a local architect who specializes in adaptive re-use, transformed a typical courtyard house, weaving the old bricks and roof tiles together in a dynamic composition that looks backwards and forward. Within the three guest rooms, with their gray brick floors and exposed rafters, platform beds were partially concealed by blonde wood screens. Breakfast was served in the largest of the three rooms, and this was also a hybrid– noodles and dumplings alongside bacon and eggs.

Layering Courtyard, a larger, more ambitious conversion is a block away, and we also explored Mirrored Courtyard, an antique store offering high-priced furniture and ceramics. I coveted a Song-era bowl that could have passed for a contemporary artwork, but its rarity raised the price to $15,000. We lunched in an exquisite tea house that serves a refined cuisine very similar to Japanese kaiseki. In each, Han had reinterpreted building traditions that are centuries old, recycling materials scavenged from old houses that were demolished in the race to modernize.

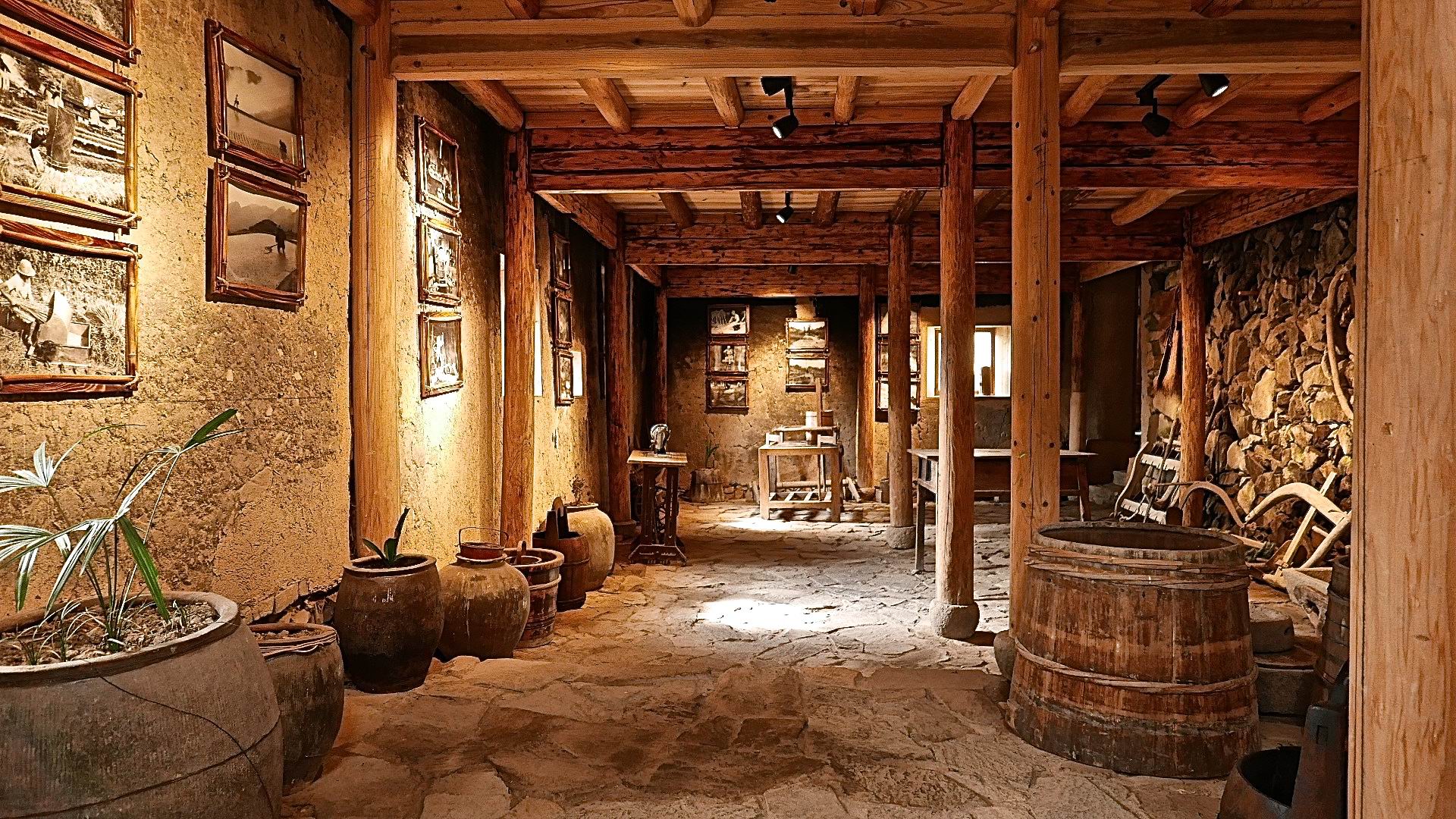

In Hangzhou, an ancient city on a lake that was once an imperial capital, we explored the new campus of the China Art Academy. Wang Shu, who won the prestigious Pritzker Prize for Architecture a few years ago, designed the rambling complex of classrooms, lecture halls and student dorms on a site of great natural beauty, and serves as Dean of the school. His architecture abstracts traditional curved roofs, upturned eaves, and pierced screen walls, using scavenged brick and tiles in inventive ways He has employed the same approach in his rehabilitation of Zhongshan, a pedestrian street in an old quarter of Hangzhou. The campus is open to the public and an added attraction is the Folk Art Museum, designed by the Japanese architect Kengo Kuma. Tiles are suspended on a metal screen and a ramp leads up through the galleries to a roof terrace.

From Hangzhou we were driven three hours south west to the provincial capital of Songyang, where we stayed in Vine House, a converted school at the heart of the old town. A dozen rooms surround a landscaped courtyard, where frogs croak in a lily pond, and a cock provides an early morning wake-up call. From here our hosts drove us into the country to explore the new buildings of Xu Tiantian, a young Beijing architect. Xu was originally invited to make some modest improvements to one of the 400 villages in Songyang County, and the authorities were so impressed by her inventiveness that they commissioned many more.

The goal of the ongoing program is to strengthen the identity of villages, creating new workplaces for local crafts and industries, and stimulate tourism in this scenic region. The flow of visitors is bound to increase when Songyang is connected to the high-speed train network next year, and the county is ready with a system of buggies and electric-powered taxis, along with a network of rural guest houses. Other provinces across China have made similar efforts to make rural life more appealing, for residents and visitors, but Songyang is a model of how to do it.

We visited a lofty workshop for the making of brown sugar, which doubles as a community center for the village, climbed a steep flight of steps to a local museum that sells dyed silk scarves, and descended to a lake-front tea house with cobbled paths and smooth concrete walls. Light spilled down from openings in the roof and a circular window framed a view out to tea plantations and distant mountains. These, and a dozen other structures, combine old and new materials—steel beams to support walls of rammed earth, concrete complementing impeccable masonry—and they feel entirely at home beside the traditional villages. And they allowed us to experience a taste of rural life–from the village headman who pulled out chairs to serve us tea in the middle of an untrafficked street, to the teacher who proudly shared the calligraphic exercises of her pupils.

As millions of Chinese migrate from farms to cities every year, and those cities become ever more congested and polluted, the countryside is seen an increasingly precious resource. And it’s more accessible to foreign visitors than ever before, although it helps to bone up on your Chinese or take along a native speaker as I did.

Michael Webb

around the world.

Latest posts by Michael Webb

- DESTINATION: Revisiting the South of France - April 30, 2024

- Exploring the Czech Republic - January 29, 2024

- Rediscovering Morocco - April 6, 2022